Væk was developed during university, as part of Game Design. We build several prototypes and had to reflect on those prototypes, which can be found under experments on play. The last assignment of the course was to try out the core loop of the final project. We had already formed groups and worked on sorting out the core loops of the game that we wanted to make. Two weeks into the process the core loop of our game-to-be had to be presented to see if our intended play experience would actually be met by what we produced that far.

At that time there was quite a lot of confusion, which loops our game would utilize. Therefore, I will instead talk about problems defining loops, how we identified them and their evolution during the development process.

Just figuring out the concept took quite some time. The group formed around the idea of creating an alternative controlled game; a digital/analog experience that would research the possibilities of an emotion relationship towards the controller. We humans understand the world by projecting our feeling upon nearly everything we encounter. There are quite a few people convinced that their smartphone is not working because it has had a rough day and will function properly if asked nicely. That is anthropomorphic thinking. It may not be true, yet it is very revealing how we perceive things we interact with as animate. We connect with things even though they offer us no clue that they are able to recognize our connection to them. How deeper can this experience become by adding live like feedback to these machines?

As we wanted to create some sort of meaningful interaction in our game, we decided upon children as a target group. This narrowed references down to only a few “games.” Most famous is the Tamagotchi. A small egg like a console that “houses” a virtual pet. The owner has to feed it, clean it and basically treat the digital entity like a living being. Yet the Tamagotchi is more of a simulator than a game. Other games we looked at were Ziff ( a physical, rearrangeable input device that invites toy like interaction for kids), Octobo (a combination of child book and plush toy that holds an iPad that provides dynamic facial feedback on interactions) and Babysitting Mama (a Wii game that ships with a plush baby into which the Wii controller has to be put).

All of these games looked fun and engaging:

Yet the assignment was due in game design and in our opinion these games were either more toylike, than actual games or they lacked specific interaction loops to meaningful connect the toy and the game to create a result that is more than the sum of its components. To consider a different approach, we strived to combine fairy tales, bedtime stories, and games. We knew we wanted to create an experience that provides time to be shared between parents and kids age four to seven.

But arranging that into loops was the real struggle, as we forgot to consider the haptic interaction between kid and toy and communication between parent and child as core loops of our game. Instead, we spend hours and days figuring out how we could improve the gameplay.

Yet, in the beginning, we had to imagine what it could feel like to hug the toy and feel it’s heart beating. With no toy, no story to speak of, we struggled to focus on one possible way to deal with the assignment.

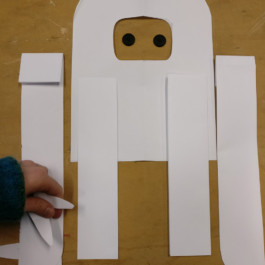

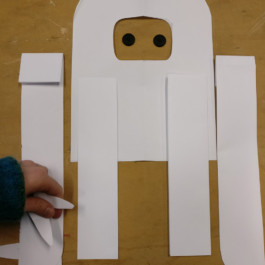

Our first prototype was closely connected to a toy I did prior to the assignment, and that was always used as a scale of what we wanted to achieve. It was a fox with a long body, that signified “nice to hug.” Our story at that time was focused on two avatars, one played and controlled by child and toy, one steered by the parent. But on the one hand the toy did not afford to be a controller for navigation and second we had only four weeks left to present a game, so we focused on one avatar instead that is played by both child and parent. As we wanted the child to control the toy and the parents to use an ordinary controller, asymmetrical gameplay, relying heavily on communication was the obvious solution for our game. The digital end was supposed to be a simple two-dimensional platformer, not too hard so the parents would not be distracted by obstacles. Their role was defined as narrator and facilitator of play.

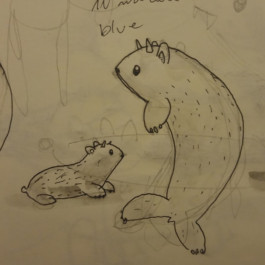

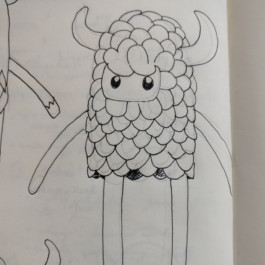

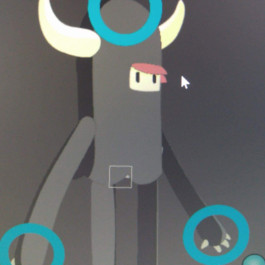

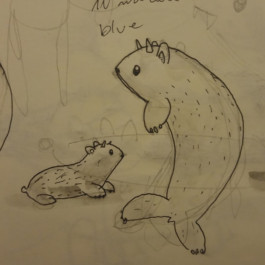

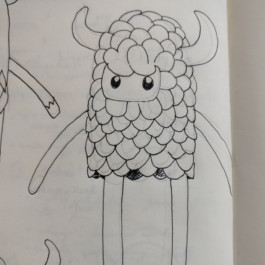

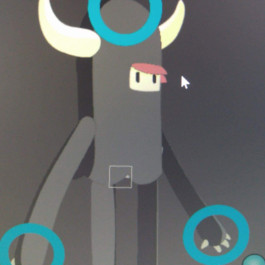

Our avatar changed from fox to seal to two iterations of the humanoid character it is now. (Only the aforementioned fox and both humanoid versions exist as physical toys.) At the same time the story became more and more free to be interpreted by the child yet more elaborated in it's mood. Talking to parents, we identified fear of darkness and of being alone as significant burdens to children. Thus our focus got more directed. Then we questioned the relationship between child and toy. At first, it was supposed to be some sort of pet to the child, but then we redefined it’s role as some kind of friend, offering to serve as a mirror to the child's semi-subconscious word and maybe even addressing the child's fears. These process happened in close collaboration with my landlord’s son. He was the first tester of any visual and idea that was produced. This feedback helped to know that the visual part of the game was working as intended for the target group. This is how the style evolved over time:

Graphics are crucial, as they provide a visual representation of the world and map out a possibility space during digital play. They dress up mathematical processes and enable players to fill dry puzzles with stories and connect emotionally to them. They convey the feeling that the avatar of a game is more than a cursor, it becomes an animate being in a world inside of the screen. But the best assets are useless if they are just used to cover up broken mechanics and flaws in the game. Controls, signifiers, and affordances have to be considered while designing games. Our toy afforded to be hugged and to be perceived as animated. So we turned it into one big button, thus registering hugs. We also added a vibrator that imitated a heartbeat. But it felt as if the child did not have enough agency while playing.

Still filling these barebones with fleshed out ideas was one of the main challenges. As the toy required more time to manufacture than it took to program first prototypes, the first digital tests were created parallel to the toy. But without it, a major part of the experience was missing. The puzzles were too easy and seemed boring. We identified our core loop to be:

Explore – Discover obstacle – Overcome obstacle – Explore further

Overcoming obstacles would involve dealing with darkness and be done in a second loop:

Parent navigates - Child feels that something is hidden – Shakes toy to reveal puzzle element – Parent uses element

To put it in different words:

Parent controls – Child feels something Parent does not know – Toy is afraid or excited – Child hugs it to encourage it – Toy bursts out positive energy – Reveals hidden secret – Parent controls again

By doing this, we mirrored a process that may be observed in everyday lives. Children often re far more sensible to emotions. Thus emotions have more influence on them. Due to their cognitive development they have a hard time distinguishing between reality and fantasy, which makes them see things that parents do not. At the same time, the child takes over as a protector and enabler for the toy. Thus it may feel empowered and will connect the act of hugging and communication to help someone else as rewarding. In my hope, this loop may also be applied into reality. But that is hard to prove and test for that. We just kept the notion and hoped to enable something meaningful with our core loop.

In retrospect due to the project's scope and technical issues, we actually achieved a lot. But, during the last period of developing the toy we were not able to reflect and reiterate as much on the game as our play-tests would require. Most feedback needs to be strengthened, the sense of progression has to be elaborated and the digital side of the game has to be questioned a lot. This will be continued next semester, as the concept seems both to be too promising and too complex to be finished after such a short duration.

Væk was developed during university, as part of Game Design. We build several prototypes and had to reflect on those prototypes, which can be found under experments on play. The last assignment of the course was to try out the core loop of the final project. We had already formed groups and worked on sorting out the core loops of the game that we wanted to make. Two weeks into the process the core loop of our game-to-be had to be presented to see if our intended play experience would actually be met by what we produced that far.

At that time there was quite a lot of confusion, which loops our game would utilize. Therefore, I will instead talk about problems defining loops, how we identified them and their evolution during the development process.

Just figuring out the concept took quite some time. The group formed around the idea of creating an alternative controlled game; a digital/analog experience that would research the possibilities of an emotion relationship towards the controller. We humans understand the world by projecting our feeling upon nearly everything we encounter. There are quite a few people convinced that their smartphone is not working because it has had a rough day and will function properly if asked nicely. That is anthropomorphic thinking. It may not be true, yet it is very revealing how we perceive things we interact with as animate. We connect with things even though they offer us no clue that they are able to recognize our connection to them. How deeper can this experience become by adding live like feedback to these machines?

As we wanted to create some sort of meaningful interaction in our game, we decided upon children as a target group. This narrowed references down to only a few “games.” Most famous is the Tamagotchi. A small egg like a console that “houses” a virtual pet. The owner has to feed it, clean it and basically treat the digital entity like a living being. Yet the Tamagotchi is more of a simulator than a game. Other games we looked at were Ziff ( a physical, rearrangeable input device that invites toy like interaction for kids), Octobo (a combination of child book and plush toy that holds an iPad that provides dynamic facial feedback on interactions) and Babysitting Mama (a Wii game that ships with a plush baby into which the Wii controller has to be put).

All of these games looked fun and engaging:

Yet the assignment was due in game design and in our opinion these games were either more toylike, than actual games or they lacked specific interaction loops to meaningful connect the toy and the game to create a result that is more than the sum of its components. To consider a different approach, we strived to combine fairy tales, bedtime stories, and games. We knew we wanted to create an experience that provides time to be shared between parents and kids age four to seven.

But arranging that into loops was the real struggle, as we forgot to consider the haptic interaction between kid and toy and communication between parent and child as core loops of our game. Instead, we spend hours and days figuring out how we could improve the gameplay.

Yet, in the beginning, we had to imagine what it could feel like to hug the toy and feel it’s heart beating. With no toy, no story to speak of, we struggled to focus on one possible way to deal with the assignment.

Our first prototype was closely connected to a toy I did prior to the assignment, and that was always used as a scale of what we wanted to achieve. It was a fox with a long body, that signified “nice to hug.” Our story at that time was focused on two avatars, one played and controlled by child and toy, one steered by the parent. But on the one hand the toy did not afford to be a controller for navigation and second we had only four weeks left to present a game, so we focused on one avatar instead that is played by both child and parent. As we wanted the child to control the toy and the parents to use an ordinary controller, asymmetrical gameplay, relying heavily on communication was the obvious solution for our game. The digital end was supposed to be a simple two-dimensional platformer, not too hard so the parents would not be distracted by obstacles. Their role was defined as narrator and facilitator of play.

Our avatar changed from fox to seal to two iterations of the humanoid character it is now. (Only the aforementioned fox and both humanoid versions exist as physical toys.) At the same time the story became more and more free to be interpreted by the child yet more elaborated in it's mood. Talking to parents, we identified fear of darkness and of being alone as significant burdens to children. Thus our focus got more directed. Then we questioned the relationship between child and toy. At first, it was supposed to be some sort of pet to the child, but then we redefined it’s role as some kind of friend, offering to serve as a mirror to the child's semi-subconscious word and maybe even addressing the child's fears. These process happened in close collaboration with my landlord’s son. He was the first tester of any visual and idea that was produced. This feedback helped to know that the visual part of the game was working as intended for the target group. This is how the style evolved over time:

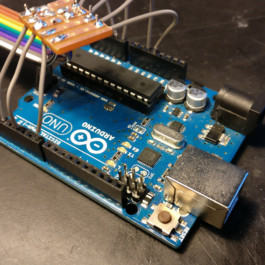

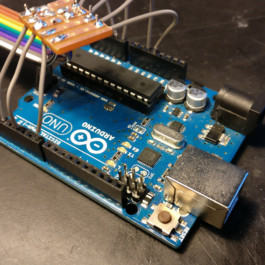

Graphics are crucial, as they provide a visual representation of the world and map out a possibility space during digital play. They dress up mathematical processes and enable players to fill dry puzzles with stories and connect emotionally to them. They convey the feeling that the avatar of a game is more than a cursor, it becomes an animate being in a world inside of the screen. But the best assets are useless if they are just used to cover up broken mechanics and flaws in the game. Controls, signifiers, and affordances have to be considered while designing games. Our toy afforded to be hugged and to be perceived as animated. So we turned it into one big button, thus registering hugs. We also added a vibrator that imitated a heartbeat. But it felt as if the child did not have enough agency while playing.

Still filling these barebones with fleshed out ideas was one of the main challenges. As the toy required more time to manufacture than it took to program first prototypes, the first digital tests were created parallel to the toy. But without it, a major part of the experience was missing. The puzzles were too easy and seemed boring. We identified our core loop to be:

Explore – Discover obstacle – Overcome obstacle – Explore further

Overcoming obstacles would involve dealing with darkness and be done in a second loop:

Parent navigates - Child feels that something is hidden – Shakes toy to reveal puzzle element – Parent uses element

To put it in different words:

Parent controls – Child feels something Parent does not know – Toy is afraid or excited – Child hugs it to encourage it – Toy bursts out positive energy – Reveals hidden secret – Parent controls again

By doing this, we mirrored a process that may be observed in everyday lives. Children often re far more sensible to emotions. Thus emotions have more influence on them. Due to their cognitive development they have a hard time distinguishing between reality and fantasy, which makes them see things that parents do not. At the same time, the child takes over as a protector and enabler for the toy. Thus it may feel empowered and will connect the act of hugging and communication to help someone else as rewarding. In my hope, this loop may also be applied into reality. But that is hard to prove and test for that. We just kept the notion and hoped to enable something meaningful with our core loop.

In retrospect due to the project's scope and technical issues, we actually achieved a lot. But, during the last period of developing the toy we were not able to reflect and reiterate as much on the game as our play-tests would require. Most feedback needs to be strengthened, the sense of progression has to be elaborated and the digital side of the game has to be questioned a lot. This will be continued next semester, as the concept seems both to be too promising and too complex to be finished after such a short duration.