Jonas Schneider and Ole Stobbe

Have you ever wondered how heroes in ancient Greek songs felt like? What did they experience between being born, growing up, living and pleasing the gods?

Divine Dilemma is set in classical Greek mythology, where two to four players struggle to overcome all obstacles fortune placed in their way. Just don’t deal with your fate like any ordinary person would. Let your life be an epic quests to be in the god’s favors!

This game let players write their own tale. Will their life be sung for eons or will they turn back to dust without anything to be remembered for? Wise decisions and being favored by the gods becomes equally important as living a prosperous life depends on balance and being aware of one’s mortality.

A narrative card game battling fate and death, finding love and living live.

A Viking game is a game that is not defined by a winner but aims for singling out the weakest player. While growing up, most agôn-based games (games that have a strong focus on competition; compare Roger Caillois) that I encountered were based on the notion of winning over others. So, the concept of playing to find the weakest player is something that does not come to my mind naturally. I learned that games should ideally consider all players equal while focusing on improving oneself to become the best; a Viking game reverses this notion. The game continues until one player proves to be weakest. You can not win, all you can do is not lose. After some thought, it occurred to me that maybe life itself could be regarded as Viking game. You ‘play’ it until you die, which is the only end state and ultimately losing condition. So my Viking game is based on living one's life. For the sake of this assignment I will abstract life into the game loop: an event occurs – decide on reaction to it –deal with outcome – encounter next event.

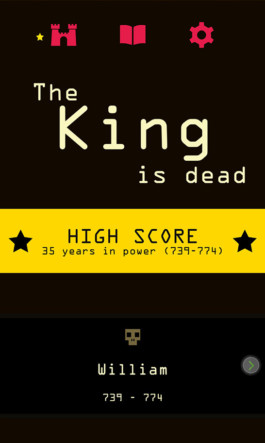

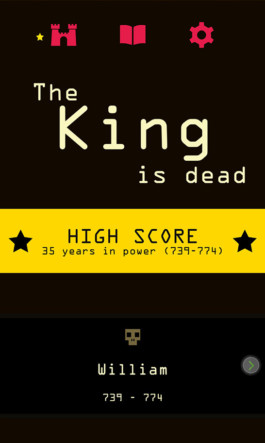

Some online research showed that Nerial’s Game Reigns (2016) incorporated a similar core loop very engaging for touch screen devices. As my previous game prototype, Card Pong proved, it is highly complicated to take a digital game and transfer it to an analog experience. So, we gave it another try and took inspiration from Reigns to create a card game based on making decisions and living as good as possible.

This is what it looks like:

As events and our decisions on them shape the story of our lives, the resulting game will always contain narrative elements and create kernels of a story of the play. Core experience was supposed to be navigating life without insulting the gods. To achieve this we aimed for a setup where decisions had to be weighted against each other without having a single, obvious best choice.

Events unfold as each new card is played. The card then introduces an event describing a situation the player’s in-game identity has to handle. The front side contains a short description, for example: ‘unexpected news;” a small image that conveys a mood and two options how players can react to it. These alternatives have to be paid by using the in-game resources “godly favor” and “earthly possessions.” After the player’s decision, the card is flipped over to reveal the outcome of this decision. Then the player could juxtapose the card to all the previous events she encountered thus creating her own biography and an overview of what happened to her. The game is set in ancient Greece, as this context offers quite an entertaining, almost soap-operaesque quality in its mythology. The gods were behaving like bored reality soap characters and kept messing with humans in quite incomprehensible ways. Most mythologic stories tell of events where they directly influenced human fate. The gods could be envious of the person’s achievement or lose interest in them if their reaction might be too dull. So the initial goal of the game was to gain “godly favor” and not become too “earthly.” Both stats were used to balance, players with too much or too little of each resource would lose the game. But that experience was not rewarding yet. The idea sounded interesting; only it was no fun at all yet. So we took another look at Reigns, and it’s affordances and feedback loops.

What makes Reigns engaging is that it incorporates different mechanics of gameplay that attract different players. You play a concession of kings and are confronted with various events and encounters. Some of them are related to personal life (find a lover, get an heir, write your memoirs, etc.); others determine the fate of your kingdom. There are four resources at stake: church, people, army, and finances. The player does not know how her decisions will influence each resource. If any resource reaches either 100 or zero percent, the play session ends, the king dies, and the player controls the next king. The binary input consists of swiping either left or right and uses the affordances of a mobile touch device in an intuitive and appealing manner. Reigns ‘feels’ awesome. At the same time, the player is never truly sure how her decisions will influence the play or what will happen next. Reigns relies on a big portion of chance, which strengths alea elements in the game. (Again, see Caillois) It partly is a game of chance. This lack of control is exciting and challenging; it spices the experience up. At the same time, nearly all feedback seems to be plausible and understandable; the game does not leave the player feeling betrayed and cheated.

Using a third term coined by Caillois, it is also safe to say that Reigns partly is a game of mimicry, of make belief. The player is roleplaying to be the King in a particular situation. She is stuck in the tension of pretending to be the king, navigating between his position and her personal world view. Even more though as the game presents her with some dilemmas, where she is aware of the gap between a presumed rewarding outcome and the ‘right’ thing to do.

After identifying these mechanics, we reconsidered which of those were afforded by our prototype and how much they were dependent on direct computational feedback. We knew, if our game kept providing inadequate feedback, it would not work as a game.

One aspect of feedback consists of scores and their representation during play. “Godly favor” and “earthly possession” were visualized by a coin that could be flipped to change from one into the other. This act of turning the coin felt rich, but having only two resources made the outcome of the game too predictable. It felt boring. To not focus on winning but make the game about losing we tried to add a health bar, but adjusting the health bar broke the experience. We continued experimenting and came up with dice. Rolling and turning them felt way better, so we created custom dice with three different sides. We also tested different weights for them, as the sensual act of rolling dice may seem unimportant, yet a cheap feel to them can influence play-experience. By adding them, all resources directly influence each other. There is a limited number of dice available. Each die can only show one status, so the number of dices is a clear signifier of maximum or minimum of each resource.

These iterations provided working mechanics as the foundation for the game. Now fine tuning to balance the game was needed. How fair and predictable are the decision’s outcomes? How are costs calculated for each decision, and how many dice does each player start with? All these variables determine how easy or hard the game is if it feels rewarding and fun, how long a play session is and lastly if the game is replayable. Yet as we only had one week to finish the game, due to scope we did not manage to balance a lot. We hope to continue working on this game in January.

Jonas Schneider and Ole Stobbe

Have you ever wondered how heroes in ancient Greek songs felt like? What did they experience between being born, growing up, living and pleasing the gods?

Divine Dilemma is set in classical Greek mythology, where two to four players struggle to overcome all obstacles fortune placed in their way. Just don’t deal with your fate like any ordinary person would. Let your life be an epic quests to be in the god’s favors!

This game let players write their own tale. Will their life be sung for eons or will they turn back to dust without anything to be remembered for? Wise decisions and being favored by the gods becomes equally important as living a prosperous life depends on balance and being aware of one’s mortality.

A narrative card game battling fate and death, finding love and living live.

A Viking game is a game that is not defined by a winner but aims for singling out the weakest player. While growing up, most agôn-based games (games that have a strong focus on competition; compare Roger Caillois) that I encountered were based on the notion of winning over others. So, the concept of playing to find the weakest player is something that does not come to my mind naturally. I learned that games should ideally consider all players equal while focusing on improving oneself to become the best; a Viking game reverses this notion. The game continues until one player proves to be weakest. You can not win, all you can do is not lose. After some thought, it occurred to me that maybe life itself could be regarded as Viking game. You ‘play’ it until you die, which is the only end state and ultimately losing condition. So my Viking game is based on living one's life. For the sake of this assignment I will abstract life into the game loop: an event occurs – decide on reaction to it –deal with outcome – encounter next event.

Some online research showed that Nerial’s Game Reigns (2016) incorporated a similar core loop very engaging for touch screen devices. As my previous game prototype, Card Pong proved, it is highly complicated to take a digital game and transfer it to an analog experience. So, we gave it another try and took inspiration from Reigns to create a card game based on making decisions and living as good as possible.

This is what it looks like:

As events and our decisions on them shape the story of our lives, the resulting game will always contain narrative elements and create kernels of a story of the play. Core experience was supposed to be navigating life without insulting the gods. To achieve this we aimed for a setup where decisions had to be weighted against each other without having a single, obvious best choice.

Events unfold as each new card is played. The card then introduces an event describing a situation the player’s in-game identity has to handle. The front side contains a short description, for example: ‘unexpected news;” a small image that conveys a mood and two options how players can react to it. These alternatives have to be paid by using the in-game resources “godly favor” and “earthly possessions.” After the player’s decision, the card is flipped over to reveal the outcome of this decision. Then the player could juxtapose the card to all the previous events she encountered thus creating her own biography and an overview of what happened to her. The game is set in ancient Greece, as this context offers quite an entertaining, almost soap-operaesque quality in its mythology. The gods were behaving like bored reality soap characters and kept messing with humans in quite incomprehensible ways. Most mythologic stories tell of events where they directly influenced human fate. The gods could be envious of the person’s achievement or lose interest in them if their reaction might be too dull. So the initial goal of the game was to gain “godly favor” and not become too “earthly.” Both stats were used to balance, players with too much or too little of each resource would lose the game. But that experience was not rewarding yet. The idea sounded interesting; only it was no fun at all yet. So we took another look at Reigns, and it’s affordances and feedback loops.

What makes Reigns engaging is that it incorporates different mechanics of gameplay that attract different players. You play a concession of kings and are confronted with various events and encounters. Some of them are related to personal life (find a lover, get an heir, write your memoirs, etc.); others determine the fate of your kingdom. There are four resources at stake: church, people, army, and finances. The player does not know how her decisions will influence each resource. If any resource reaches either 100 or zero percent, the play session ends, the king dies, and the player controls the next king. The binary input consists of swiping either left or right and uses the affordances of a mobile touch device in an intuitive and appealing manner. Reigns ‘feels’ awesome. At the same time, the player is never truly sure how her decisions will influence the play or what will happen next. Reigns relies on a big portion of chance, which strengths alea elements in the game. (Again, see Caillois) It partly is a game of chance. This lack of control is exciting and challenging; it spices the experience up. At the same time, nearly all feedback seems to be plausible and understandable; the game does not leave the player feeling betrayed and cheated.

Using a third term coined by Caillois, it is also safe to say that Reigns partly is a game of mimicry, of make belief. The player is roleplaying to be the King in a particular situation. She is stuck in the tension of pretending to be the king, navigating between his position and her personal world view. Even more though as the game presents her with some dilemmas, where she is aware of the gap between a presumed rewarding outcome and the ‘right’ thing to do.

After identifying these mechanics, we reconsidered which of those were afforded by our prototype and how much they were dependent on direct computational feedback. We knew, if our game kept providing inadequate feedback, it would not work as a game.

One aspect of feedback consists of scores and their representation during play. “Godly favor” and “earthly possession” were visualized by a coin that could be flipped to change from one into the other. This act of turning the coin felt rich, but having only two resources made the outcome of the game too predictable. It felt boring. To not focus on winning but make the game about losing we tried to add a health bar, but adjusting the health bar broke the experience. We continued experimenting and came up with dice. Rolling and turning them felt way better, so we created custom dice with three different sides. We also tested different weights for them, as the sensual act of rolling dice may seem unimportant, yet a cheap feel to them can influence play-experience. By adding them, all resources directly influence each other. There is a limited number of dice available. Each die can only show one status, so the number of dices is a clear signifier of maximum or minimum of each resource.

These iterations provided working mechanics as the foundation for the game. Now fine tuning to balance the game was needed. How fair and predictable are the decision’s outcomes? How are costs calculated for each decision, and how many dice does each player start with? All these variables determine how easy or hard the game is if it feels rewarding and fun, how long a play session is and lastly if the game is replayable. Yet as we only had one week to finish the game, due to scope we did not manage to balance a lot. We hope to continue working on this game in January.