Arendse Løvind, Atanas Slavov and Jonas Schneider

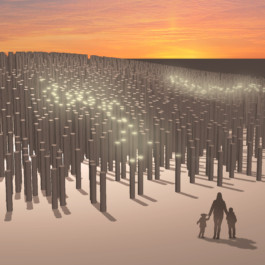

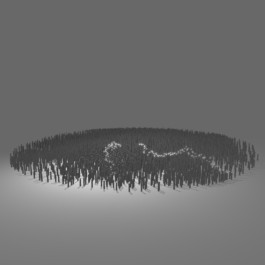

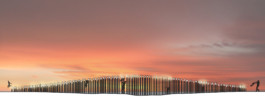

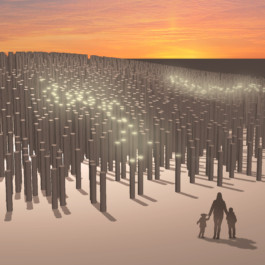

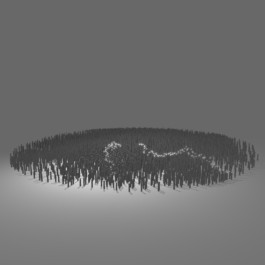

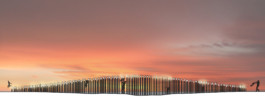

Imagine a circular field of what looks like columns or abstracted trees. These trees are of varying height and just like a real forest do not follow a clear grid. Some trees are more tightly clustered, others from small clearing between them. With their dark trunk, that is made of rubber, and their bright tips, the trees look surreal and inanimate.

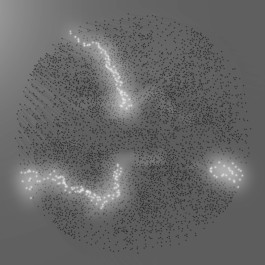

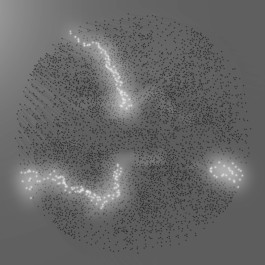

From time to time, some treetops start to light up for a short duration. The light seems to be moving into the forest. You follow the light and enter the playground. The ground beneath you is soft and will dampen your falls, you are nor afraid to fall. Once you touch a tree trunk, it lights up only to vanish after a short time. By that, you always perceive the light as a movement; wherever you go, an illuminated trail shows where you came from.

The light color by default is white, but it can be changed by the visitors of the light forest. You just have to log in the accompanying app and can customize how the trees will react to touch. You can draw patterns and make people follow you.

If no one interacts with the trees for a longer while the forest can either replay ways people interacted with it, it can illuminate itself, or it can be customized by users via the internet. It can be used to communicate, to decorate or become part of some play between individuals trying to

Verbs: run, climb, hide, seek, touch, see, explore, imagine, sneak, dodge, contemplate, observe

“All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the 'consecrated spot' cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground. [All places of play] are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.” (Huizinga, 1955)

“In a very basic sense, the magic circle of a game is where the game takes place. To play a game means entering into a magic circle, or perhaps creating one as a game begins.“ (Salen & Zimmermann, 2003)

In retrospect, this task seems to be aimed towards learning to provide a structure of play (which is also closely connected to level design), yet our group focused on an entirely different approach. We wanted to create a space that only utilizes one prop yet offering a vast space of possibilities for interaction. We want our playground to afford individual interpretations of unstructured play for people of all ages. Caillios calls this type of play paidia. I would argue that structured play on playgrounds, whether done individual or in groups, mostly starts out as unstructured free-play. Then rules begin to emerge. They slowly evolve until the play is structured and has some outcome. This result can dynamically change and adapt any time. Still in that case play has changed from paidia to ludus, a structured form of play. As adults are aware of all the games they played, they may often skip paidia and start engaging in a structured experience that was fun when they were younger. But mostly they are not playing but reenacting how they played. I would call this make believe play. This is partly caused by how playgrounds are normally designed.

When talking about playgrounds miniaturized child-friendly version of the world come to mind. They have to be good to overlook so parents can watch over their children. Playgrounds are sheltered places of play; in contrast to playing fields they provide minimal structure to allow for various interpretations. Thus they can be seen as a direct translation of what Huizinga coined “magic circle.” There is no question that they are designed for children. Needless to say that places that afford optimal conditions for child play don’t have to be suited for adult play. Adults do not want to be observed; they need a safe space that ensures them that no one watches while they make a fool out of themselves. As they are They want a feeling of vertigo; in Caillois calls this ilinx, yet situations that provide a safe way of living through these experiences for kids are plain boring for an adult. This only applies if the whole design of the play structure actually allows them to enter and use it. If it is too small and will not support their weight, they have no chance of using the play element.

All these observations made us think about places that may not be dedicated playgrounds, but still afford all kinds of play, regardless of age and size.

While many examples come to mind, I will only talk about the strangest place of play possible: the Holocaust memorial in Berlin, Germany. It is a beautifully designed monument, consisting of 2711 concrete blocks. The blocks are arranged in a rigid grid and vary in high and size. The ground is also not even but rises and falls without understandable logic.

It is a place to remember six million Jews that were killed in Germany during World War Two.

A serious place, in the heart of Berlin. No place of play, one would say. Yet this place invites for play; it affords to hide and seek, tag, jumping around and climbing on the concrete elements. In this regard, these affordances crash completely with the intended use of the memorial.

What I think is fascinating is how the holocaust memorial invites people of all ages to play. Players are not always visible; they feel protected by the structure of it. One should just imagine how people would play if all these possibilities of play happened in a context that would encourage people to be play- and joyful.

The following question then is: What setting allows adults and kids alike to engage in a playful way?

Considering art installations by Tomas Saraceno, Olafur Eliasson or Daan Roosegaarde (just to mention some examples. Much more could be listed here), we observed that all these artists presumably willfully included playful interactions into their installations. And grown people are willing to engage with them in a playful manner. Art seems to excuse what could under different circumstances be considered juvenile behavior. Children do not need an excuse for that, yet they need to be watched by parents. In a context like the light forest, a compromise may be found. What it is lacking are clear signifiers of what can be done with the trees. The structure affords a lot of different games and playful interaction, yet players are only provided minimal signifier of how they may interact. Reactive light can serve as an adamant form of engagement. But disregarding the app, the light forest depends on people interacting with it. As it is, it resembles more a spatial version of some simple toy than an actual playground. Everything can become a toy or rather be used as a toy, so this is not a significant achievement. Every space can be reused as a playspace. Maybe our structure makes it easier than other spaces to engage with it in a playful way. Still, we tried to create a playground, but we ended up with a mixture of installation, spatial toy, and playful place. (Also the playfulness of the structure is somewhat obstructed by the monotonous form of visualization. They look graphically pleasing but provide a strong air of art and neglect playfulness in design)

Arendse Løvind, Atanas Slavov and Jonas Schneider

Imagine a circular field of what looks like columns or abstracted trees. These trees are of varying height and just like a real forest do not follow a clear grid. Some trees are more tightly clustered, others from small clearing between them. With their dark trunk, that is made of rubber, and their bright tips, the trees look surreal and inanimate.

From time to time, some treetops start to light up for a short duration. The light seems to be moving into the forest. You follow the light and enter the playground. The ground beneath you is soft and will dampen your falls, you are nor afraid to fall. Once you touch a tree trunk, it lights up only to vanish after a short time. By that, you always perceive the light as a movement; wherever you go, an illuminated trail shows where you came from.

The light color by default is white, but it can be changed by the visitors of the light forest. You just have to log in the accompanying app and can customize how the trees will react to touch. You can draw patterns and make people follow you.

If no one interacts with the trees for a longer while the forest can either replay ways people interacted with it, it can illuminate itself, or it can be customized by users via the internet. It can be used to communicate, to decorate or become part of some play between individuals trying to

Verbs: run, climb, hide, seek, touch, see, explore, imagine, sneak, dodge, contemplate, observe

“All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the 'consecrated spot' cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground. [All places of play] are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.” (Huizinga, 1955)

“In a very basic sense, the magic circle of a game is where the game takes place. To play a game means entering into a magic circle, or perhaps creating one as a game begins.“ (Salen & Zimmermann, 2003)

In retrospect, this task seems to be aimed towards learning to provide a structure of play (which is also closely connected to level design), yet our group focused on an entirely different approach. We wanted to create a space that only utilizes one prop yet offering a vast space of possibilities for interaction. We want our playground to afford individual interpretations of unstructured play for people of all ages. Caillios calls this type of play paidia. I would argue that structured play on playgrounds, whether done individual or in groups, mostly starts out as unstructured free-play. Then rules begin to emerge. They slowly evolve until the play is structured and has some outcome. This result can dynamically change and adapt any time. Still in that case play has changed from paidia to ludus, a structured form of play. As adults are aware of all the games they played, they may often skip paidia and start engaging in a structured experience that was fun when they were younger. But mostly they are not playing but reenacting how they played. I would call this make believe play. This is partly caused by how playgrounds are normally designed.

When talking about playgrounds miniaturized child-friendly version of the world come to mind. They have to be good to overlook so parents can watch over their children. Playgrounds are sheltered places of play; in contrast to playing fields they provide minimal structure to allow for various interpretations. Thus they can be seen as a direct translation of what Huizinga coined “magic circle.” There is no question that they are designed for children. Needless to say that places that afford optimal conditions for child play don’t have to be suited for adult play. Adults do not want to be observed; they need a safe space that ensures them that no one watches while they make a fool out of themselves. As they are They want a feeling of vertigo; in Caillois calls this ilinx, yet situations that provide a safe way of living through these experiences for kids are plain boring for an adult. This only applies if the whole design of the play structure actually allows them to enter and use it. If it is too small and will not support their weight, they have no chance of using the play element.

All these observations made us think about places that may not be dedicated playgrounds, but still afford all kinds of play, regardless of age and size.

While many examples come to mind, I will only talk about the strangest place of play possible: the Holocaust memorial in Berlin, Germany. It is a beautifully designed monument, consisting of 2711 concrete blocks. The blocks are arranged in a rigid grid and vary in high and size. The ground is also not even but rises and falls without understandable logic.

It is a place to remember six million Jews that were killed in Germany during World War Two.

A serious place, in the heart of Berlin. No place of play, one would say. Yet this place invites for play; it affords to hide and seek, tag, jumping around and climbing on the concrete elements. In this regard, these affordances crash completely with the intended use of the memorial.

What I think is fascinating is how the holocaust memorial invites people of all ages to play. Players are not always visible; they feel protected by the structure of it. One should just imagine how people would play if all these possibilities of play happened in a context that would encourage people to be play- and joyful.

The following question then is: What setting allows adults and kids alike to engage in a playful way?

Considering art installations by Tomas Saraceno, Olafur Eliasson or Daan Roosegaarde (just to mention some examples. Much more could be listed here), we observed that all these artists presumably willfully included playful interactions into their installations. And grown people are willing to engage with them in a playful manner. Art seems to excuse what could under different circumstances be considered juvenile behavior. Children do not need an excuse for that, yet they need to be watched by parents. In a context like the light forest, a compromise may be found. What it is lacking are clear signifiers of what can be done with the trees. The structure affords a lot of different games and playful interaction, yet players are only provided minimal signifier of how they may interact. Reactive light can serve as an adamant form of engagement. But disregarding the app, the light forest depends on people interacting with it. As it is, it resembles more a spatial version of some simple toy than an actual playground. Everything can become a toy or rather be used as a toy, so this is not a significant achievement. Every space can be reused as a playspace. Maybe our structure makes it easier than other spaces to engage with it in a playful way. Still, we tried to create a playground, but we ended up with a mixture of installation, spatial toy, and playful place. (Also the playfulness of the structure is somewhat obstructed by the monotonous form of visualization. They look graphically pleasing but provide a strong air of art and neglect playfulness in design)